The Southern Cross Gliding Club has evolved from the amalgamation of several early gliding clubs that sprang up around Sydney, and settled at Camden Airport.

The Early History of Southern Cross Gliding Club

Sydney Button built his Zogling Primary Glider and test flew it in 1941 on the paddocks at Matraville, right next to Mascot Airport. He taught himself to fly by getting a friend to operate his Essex car which had the back wheel jacked up and fitted with a drum full of wire. He learned take-offs and landings first (which is reasonable) before going a bit higher.

The AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australia) Gliding Club started in July 1944 and purchased Button's Primary Glider, did it up, and test flew it on 1st January 1946 at Doonside. As people from outside AWA were starting to join the club, it was decided to change the name to Southern Cross Gliding Club. The inaugural meeting was held on the 8th January, 1948 at Respins Restaurant, 175 Pitt Street, Sydney.

The club moved from Fleurs Airstrip to Camden in 1953 where student pilots dragged the primary up and down the main strip on a 25m long wire and tried not to crunch it down too hard while they learnt to glide. A picture of the beloved machine is on the clubhouse wall. Power traffic in those days was one Tiger Moth a fortnight.

When Edmund Schneider was helped to set up in South Australia by the GFA, the Kookaburra two-seater glider soon appeared on the market. The 10 club members worked themselves into the ground over a long period, organising bottle drives, raffles and loans to scrape the purchase price together. The Kooka arrived in November 1955.

Membership had always been in the doldrums until then, but with a new Kooka and new winch, people appeared from everywhere and membership had to be limited to 40 in 1957. Well known 'new' members such as Werner Geisler, Roger Woods and George Detto, joined late in the '50s. AWA foundation member Merv Waghorn became the club's first Honorary Life Member.

Miro's System

Some of our more recent club members may be unfamiliar with the name 'Miro Vitek', however, to many, Miro will be fondly remembered as 'The Man in the Tower'

What is beyond dispute is that the club remains operating from Camden solely due to the efforts of this one man, and arguably owes its continuing existence to him too.

Many people from the old days have written tall tales but true about the gliding characters of yesteryear. I decided to narrow the focus and orient my approach towards gliding in New South Wales and how it related to the Southern Cross Gliding Club.So this is the story of our Club, and how and why it all got started.The first "glider" flight in Australia was made in December 1909 by George Taylor at Narrabeen, NSW. A special memorial has been erected opposite the Narrabeen Post Office to commemorate this feat. Taylor's partner was a young fellow by the name of Edward Halstrom who was to become a household name in Australia for his gas powered Silent Knight home refrigerators of the 1950s and his private zoo of rare animals.

These were the days of the hang glider, not to be confused with the modern ones with all sorts of control devices and harnesses on them. No, these had two poles running fore and aft which fitted under the pilot's armpits and had him literally hanging under the glider. Part of his job was to attempt to control the machine by sliding forwards and backwards and swinging to the left and right. The other part of the pilot's job was trying not to slip off.

I spoke to Stan Rose who was later to become Secretary of the Southern Cross Club about the early days. In 1930, he saw the Granville Club's glider and was very impressed with it. Being a lad of 15, he went home and found a design of a hang glider in "Chums Annual" and decided to build it. It had about a 5 metre wingspan and was made of bamboo tied together with cord fishing line.

When the wings were ready for covering the only logical material was some bed sheets and these proved ideal although his mother put on no end of a performance when she found out. Ah, one of the first of many little differences of opinion caused by gliding.

So with the wing covering held on with flour and water glue, it was ready for test flying. The site was Duck Creek at Auburn and it was blowing a good westerly. Stan got up a bit of a run and with a good angle of attack, the thing jumped about five feet into the air. Next it dropped one wing, zoomed into the creek and clobbered the only tree stump in sight.

Stan suffered minor structural damage and when assisted home by his mate, was given a good walloping by his father who then tore down to the creek and burnt the crumpled remains of the machine. Stan was grounded!

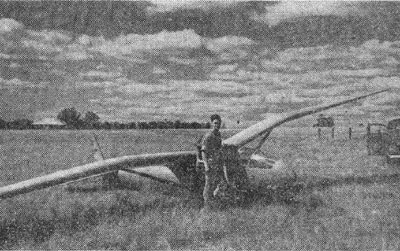

SCGC Sec. Stan Rose in 1949 in SCGC Zogling Primary Glider

As Primary gliders were at least somewhat controllable, they started to become fashionable and a number of groups started to build them. The Primary glider consisted of a simple rugged fuselage, open and looking like a country farm gate, while the wings were of slab appearance with a wing section that was practically unstallable. The pilot sat at the front end of the 10 cm wide fuselage on a simple seat, and watched the countryside pass between his knees. The Secondary glider was slightly soarable in hill lift and pilots graduated to one of these machine when they learned to "land" rather than "arrive". Very few clubs had Secondarys though.

Harry Ryan, who was later the CFI of the Southern Cross Gliding Club, was one of the early pioneers of gliding. He had his first flights with Martin Warner and Alf Pelton who operated a German Primary glider from the sandhills at Cronulla in 1931.

In 1936, this group tried ridge soaring at Saddleback Mountain near Nowra. Whilst there, the group had some success and one member Phil Hamilton, is said to be the first man to soar in Australia, in the sense that he climbed above the height of release.

Then thermals were discovered and in Victoria in October 1937, Ron Roberts put his name in the record books by using a new "circling" technique to gain height.

The first big step in modern gliding in NSW was in 1939 when Dr George Heydon, a Macquarie St medico imported a Slingsby Gull 1 from England. This was a true sailplane and a forerunner of the machines of today. It had a cockpit and windshield, and using his Tiger Moth VH-AGK as a tug, Doc Heydon formed the Sydney Soaring Club. The group also flew from Narromine in 1940 and were the first to try cross-country flying in NSW.

Of particular interest were the efforts of a 17 year old lad called Sydney Button who decided to build a Zogling Primary glider. This machine was eventually to become the backbone of the Southern Cross Gliding Club. It was originally an open fuselage machine and had bracing wires above and below the wings called Landing and Flying Wires which took the strains during these operations. Despite the shortages of materials in World War 2, he completed the machine and test flew it at Matraville in 1941.

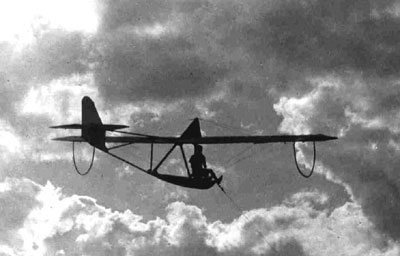

Basic Primary Glider @ Box Hill NSW circa 1940

Sydney Button wrote a graphic description of the test flights:

"I test-flew the Primary using my Essex car as a winch by bolting a drum to a jacked-up back wheel. The only previous flying instruction I'd had was in one of Jack Munn's gliders called the 'Heron', a biplane." (The Southern Cross Gliding Club later acquired this machine as a monoplane due firstly to a prang and secondly due to a lack of materials which resulted in a quick-as-a-flash redesign. It was not successful).

"In the Primary, I got as far as straight hops up to 50 ft. From then on I learnt by trial and error. I used to get all keyed up inside and was terribly excited by the time the Primary was assembled and ready for flight. During the excitement, I connected the control wires to the ailerons the wrong way and it took me three attempts at taking off to realise what was wrong.

"Each time I tried to lift the wing off the ground while skidding along, it just rubbed the sandy ground harder until the machine struck a sandy patch of pretty rough ground. The nose dug into the sand, the machine turned completely over and I was thrown off onto the back of my neck into the sand, taking part of the seat and the safety belt with me.

"After righting the machine I did not let this deter me. I fixed the trouble by strapping the seat back on with wire and put the safety belt around the kingpost" (the main vertical post in the fuselage) "and then around my body.

The Heron Biplane circa 1941

"During flights after that, most of the people on the ground thought I left the machine each time I dropped the tow cable as the momentum I gathered during the climb and release, forced me up the king post and I was suspended momentarily and then flopped back into the seat. A queer sensation believe me."

Another adventurous group formed the Beaufort Gliding Club in December 1942. They had a primary and flew from any handy paddock. They often flew from a hill at Chullora near where the Chullora Railway Workshops used to be.

One of the group Vic Dawson, built a power plane but due to the war couldn't find an engine for it. So he built a large nose which went nearly two metres in front of the pilot to make up for the weight of the engine, and modified the undercarriage to incorporate a full size motor bike wheel. It was innovations like this that characterised this period. But it flew! Later on in 1944, a group purchased it and formed the Phoenix Gliding Club.

Another unusual machine was Ken Kirkness' water glider "Miss Mercury". The side by side two-seater had broad sponsons on each side of the wide fuselage and a tapered high wing. For initial testing, a wheeled undercarriage was fitted and several flights were made. Water take-offs with the help of a speedboat on Sydney Harbour were not successful due to the hemp rope getting wet and sinking, and then becoming very heavy, among other things.

Meanwhile some apprentices at the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation had become interested in gliding. They found some plans in a library book and built a Primary from bollygum timber. Members of this group were Ray Ash, Allan Ash (later of Australian Gliding fame) and Leo Diekman. They formed the Cumberland Gliding Club and flew in 1945. They were later all members of the Southern Cross Gliding Club.

Another group was started by Jack Munn who designed and built the Falcon. They formed the Sydney Metropolitan Gliding Club and flew at Bunerong Park, about a kilometre from Mascot Airport. They flew by day and night and records show that the group often flew until midnight if the moonlight was bright enough. To help with night landings, a motor bike headlamp was fitted to the front of the machine and a motor bike battery tied inside the nacelle. When coming in to land, at a few feet off the ground, the pilot used his left hand to clip a lead onto the battery terminal.

Of all the groups to start, the most important from our point of view was the AWA Gliding Club. This was formed by members at Amalgamated Wireless (Aust) at Ashfield, and was open to people who worked there. Members included Harry Ryan, Gil Miles, Don Hatton and later Bob Krick. The club started in July 1944 and they purchased the Zogling Primary built by Sydney Button. It was rebuilt in the club's workshop at Croydon and fitted with wooden wing struts in place of the wires, as well as a small enclosure called a nacelle, which streamlined the pilot and gave him a false sense of security. They test flew it on 1st January 1946 at Doonside.

Harry Ryan with the Gull sailplane circa 1945

In 1946 the AWA Club moved to a disused wartime emergency strip just west of Cabramatta called Fleurs Airstrip which was only 3 Km away from the Doonside airfield. It was to become more or less a permanent home for gliding operations. Being on the bend of a river, it used to flood regularly and when a hanger was finally built the machines were always lifted up on top of 200 litre drums as a safety measure. On visiting the strip after one of these floods, the first job was always to retrieve the toilet hut which always seemed to be a couple of kilometres downstream.

At the end of '46 things were pretty busy at Fleurs. The clubs operating from there were the AWA Club, Sydney Metropolitan, Cumberland-Phoenix (now amalgamated) and occasionally Sydney Soaring. This prompted an article to appear in the "Eagle Gliding and Flying Magazine" as follows:

"Warning to Onlookers. Due to the increasing popularity of gliding in Sydney, stricter supervision at Fleurs Airstrip (mecca of Metropolitan Motorless Flying enthusiasts) was advocated at a recent meeting of the Sydney Metropolitan Gliding Club. On Six Hour Day the strip was very congested with gliders, cables and visitors. Due to a strong crosswind machines were taking off from both ends of the strip at the same time."

Also at Fleurs was a Prufling Primary owned by Gil Miles who was to become a very famous CSIRO radiophysicist. Although the machine only had one seat, Gil sometimes took his young son for flights by strapping him to the kingpost by means of a leather belt. He TOLD me the boy enjoyed it. This machine was acquired many years later by the Illawarra Club in Sydney.

SCGC Operations at Fleurs Airstrip in the Late 1940s

Now that World War 2 was over, Sydney Soaring was showing how things should be done. In 1945 they flew from Parkes to Melbourne in two hops. The first by Martin Warner was from Parkes to Jerilderie, about 200 miles(320Km). Harry Ryan then took his turn and flew to Melbourne, a distance of 165 miles. He could have gone further but at 6500 ft. over Melbourne and with Port Phillip Bay stretching in front of him, he decided to land at the best spot around which was Essendon Airport. This caused the Civil Aviation people (DCA as they were at the time) to have a few well chosen words about such the unwarranted drop-in on their aerodrome.

Martin Warner also made his mark in December 1945 by setting Australian Height Records which stood for nearly a quarter of a century. From a 900ft launch he set an Absolute Height Record of 12,000ft with a Gain of Height of 11,000ft. Naturally in those days he had no oxygen.

Some well written articles started to appear in magazines such as the one by Ted Baker of the AWA Club, describing an incredible electric variometer which was identical to some of our modern instruments except he used heated wire coils instead of the more modern thermistors. This no doubt started much of the research into electric variometers.

Another article by Harry Ryan was called the Scientific Art of Thermal Soaring. His article is of great interest because the things which were merely a pipe dream to him, we now accept as natural everyday occurrences. He described how future training could be carried out in two seater gliders and how an instructor might even do advanced training such a teaching people how to catch thermals. He wrote:

"It seems highly probable that when we have settled down in peace-time conditions, the beginner will be able to drive along to his local club, book an instructional flight with a competent instructor and then be towed by an aeroplane to a height of several thousand feet, there to be cast off and receive instruction during the whole flight right up to the final moment of landing.

"The possibilities are also that on his first solo flight he will be maintaining full radio communication with his instructor on the ground. Quite a change from the days when a pupil was catapulted over the side of a hill in a primary glider."

Gliding continued to grow and in 1946 there were 20 gliding clubs in Australia. Civil Aviation were now convinced that gliders really flew, thought some form of indirect control was necessary and thoughts towards a gliding federation around Australia slowly germinated.

Meanwhile the AWA Club, having amalgamated with the Granville Club, was battling on with its Primary. A typical "good" day was recorded as "4 hops, 3 flights, Total 7 launches".

The club decided that the membership should no longer be limited to AWA employees and in July 1946 accepted its first "open" member Reg Todhunter.

Many of the other clubs were folding up for different reasons and the remaining members and equipment were inherited by the AWA Club. Allan and Ray Ash came over from the Cumberland-Phoenix Club which closed for want of a machine. In June 1947 the Sydney Metropolitan Club gave its equipment to the AWA Club following the death of Jack Munn and Sid Taberlet in the home-built V tailed "Wanderlust".

Apart from the Sydney Soaring Club, the AWA Club was the only remaining club in the Sydney area and it was the only training club. As it consisted of bits and pieces of so many other clubs and was no longer for AWA employees only, it was decided to think of another name for it. Towards the end of 1947 it was briefly known as the Western Suburbs Gliding Club. But at the end of 1947 the club was renamed The Southern Cross Gliding Club.

So our club, that complex mix of so many of the previously mentioned groups, held its first meeting under its new name on 8th January 1948. It was held at Respins Restaurant, 175 Pitt Street, Sydney. The business was to elect a committee and to adopt the club's first constitution.

The Club's first Committee was:

- Dr. George Heydon – President

- Harry Ryan – Captain and C.F.I.

- Trevor Leck – Vice Captain

- Bob Krick – Secretary

- Les Wright – Treasurer

The entrance fee was $4.20 (two pounds and two shillings, otherwise known as two Guineas) and the Annual Subs were $6.30. Flying fees were 15c for a circuit or other flight, 10c for a hop and 5c for a skid. Skids and hops were part of the training program where the pupil climbed into the single seat Primary and proceeded to learn solo to control the glider on ground runs (skids). He then progressed to learning take-offs and landings (hops).

On the 24th March 1948 the Club started the "Share Loan System" where members loaned the Club money to buy materials to build another glider or perhaps even a sailplane.

This was not to be, as in October 1948, Don Pitt undershot on approach, skittled a small tree and the primary required a complete rebuild. It was back to the workshop where all the members gave their time to do the work, the funds were eaten up for materials and everyone hoped to be flying again soon!

Then some sailplanes came up for sale. These were ready-made machines which were a rarity in those days because if you wanted a machine you normally built it. The costs otherwise were unbelievably high! A club meeting in March 1949 was told… "There are two sailplanes for sale in Sydney. A Grunau Baby 2 at $500 and a Slingsby Gull owned by the Sydney Soaring Club for $800." Despite the enormous cost (for those days), some keen members found the money could be raised but after a long talk by the C.F.I Harry Ryan, it was decided that "the Club in its present state could not afford to successfully operate machines of this type." This was a reasonable statement as, with the high wrecking rate of some rather rough pilots, the club would have been bankrupt in no time.

However some of the members thought that the flying of primaries had gone far enough and decided to leave the Club and form a new group with a sailplane. These were Allan and Ray Ash, Bob Krick and Leo Diekman who along with Aub Parsons and Fred Hoinville formed the Hinkler Club at the beginning of 1949. Fred was to become very well known in Sydney for his skywriting during the 1950s using his Tiger Moth fitted with a special smoke generator. His aerial advertisements floated over football matches, surfing carnivals and so on, and if the winds were a bit changeable, one word or a letter of the advertisement would be seen to go in one direction while the rest went in the other.

At the first Annual General Meeting of our Club in July1949, the members elected our first Honorary Members. They were Harry Ryan, Dr George Heydon and Merv Waghorn. These peoples' names were to re-occur again and again in gliding circles and much of the success the Club was yet to have was due to them.

Southern Cross Zogling Primary with Nacelle 1954

Gliding was spreading in Australia and it was starting to become organised. The Gliding Federation of Australia was constituted in 1950 and Allan Ash started the magazine Australian Gliding in December 1951. Allan edited AG for many years, running it as a private loss-making venture which he miraculously wrote in his spare time. Eventually in 1959 Allan could not cope with the workload anymore (or the cost) and publication ceased until the GFA finally took it over in 1961.

Late in 1953 the NSW Gliding Association decided to hold a "gliding pageant" at Camden. The Hinkler and Sydney Soaring Clubs were already flying their sailplanes from this site. Although the Southern Cross membership was down to five, they loaded the old Primary onto an antique Bedford truck and decided to attend the pageant as well.

They were very impressed with the long smooth Camden runways and decided not to return to Fleurs Airstrip which was destined to be taken over by the CSIRO for the Maltese Cross Radio Telescope. Besides Camden was totally deserted apart from a few gliding people and a locally owned Macarthur-Onslow Hornet Moth which rarely flew.

The aerodrome area was originally a race track owned by Arthur Macarthur-Onslow. In 1919 a film called "Silks and Saddles" was being made which required a race between a horse and an Avro 504K, and the Camden track was ideal for shooting this sequence. Edgar Percival of Percival Aviation (responsible for the Percival Gull and Proctor) who landed the first plane there for the film, took Arthur's schoolboy son Edward for a ride in the little Avro. Edward later took lessons and as soon as he was able, the horses were out and the planes were in. Camden became Australia's first private aerodrome. Edward Macarthur-Onslow became a great personality in aviation and formed the Macquarie Grove Flying School which by 1939 employed more than thirty people in the workshops at Camden Aerodrome servicing about a dozen aircraft at all levels, including engine overhauls and propeller manufacture.

Macquarie Grove Flying School Maintenance at Camden 1939

When World War 2 came, Edward Macarthur-Onslow made the aerodrome available to the Commonwealth Government "for the training of Australian war pilots". Then the RAAF moved in, and then the Americans, the elegant Macquarie Grove House on the aerodrome was turned into an officer's mess and the sergeants made even more of a "mess" of Hassell Cottage at the top of the hill. Tarmac flowed everywhere, the quietness was shattered forever and the records blur somewhat out of kindness. The Hon. Mr Fairburn, the Minister of the Crown who was given the use of the aerodrome died during the war and the verbal assurances that the drome would be returned to the family died with him. The aerodrome was now Commonwealth Property!

What the gliding people saw in 1953 was an almost intact example of a WW2 Air Force training base. Near the top of the hill at the bend in the road was a sentry box with boom gate and khaki painted wooden huts stretched in rows right down the hill to the hangers which were full of unwanted aircraft, mainly Avro Ansons. There was a khaki wooden control tower built on tall crossed-braced poles on the high side of the intersection of the main strip and the taxiway (which was the original cross-strip). Hardy souls who climbed this rickety structure all said "Never again!" The sand hills to the south of the field were full of cannon and machine gun rounds where the aircraft guns had been tested. That so much should have remained in 1953 was remarkable. But no one else visited the place and it was like an old movie set of WW2. The gliding people were even given the use of a few wooden huts.

Again from WW2 were some war-surplus gliders which had been used for training wartime pilots. In 1946 a batch of 54 unused Pratt-Read TG-32 sailplanes were offered for sale at $200 each (the original cost was $10,000 each - and that was 1940s dollars) as well as many others. The Pratt-Reads were massive machines and were usually pulled a couple at a time by a DC3. Another large machine, a Schweitzer TG3 two-seater, found its way here in the 1950s and was acquired by Fred Hoinville. It was impossible to car launch it due to its weight and when his Tiger Moth was hitched on to it, it groaned and refused to climb. Heads were scratched and by experimentation it was found that using the high-tow method of launching (which was used because the English used it) was not as efficient as low-tow which launched the TG3 slowly but effectively. Soon it was found that everything climbed better behind Fred's Tiger in low tow and it became the standard for Camden and eventually Australia. Mind you, there are still some overseas people who still say we are wrong despite the figures of proof!

By now a stream of European WW2 displaced persons and migrants were making their way to Australia. Many were very talented while some had much more front than talent. After the first few minutes of meeting some of the latter, the talk would soon get around to the vast amount of flying experience they had in gliders and a complete set of glider plans they had designed, would emerge from a battered leather briefcase. We were told these plans could easily be put into practice, and if only we had the money, could be built, flown and bring world recognition all by the end of the week!

Some were genuine and highly skilled. When Edmund Schneider and family (including young Harry) expressed interest in migrating, their reputation was well known. They had built machines in their home town of Grunau in Germany and named one of their most successful sailplanes after the town. With considerable financial assistance from our gliding community they were helped to come here and set up a factory in South Australia. They were soon able to offer a number of machines including a two-seater sailplane, the Kangaroo. This identified a whole new way to train and the machine captured many people's imagination. The Hinkler Club decided that something should be done about expanding, and the Kangaroo two seater seemed to be a good aircraft upon which to build a training program.

So an advertisement was placed in a Sydney newspaper and a flock of enthusiastic people turned up at the Malvern Hall at Croydon. However at the last minute the meeting had to be told that unfortunately finance could not be found for such a scheme and that the whole deal was off.

Most of the flock went home except a small group who formed a rival meeting at the other end of the hall. They decided to form their own group and try somehow to fly. Members included Frank Geach, Jim Rawlings and John Postlethwaite.

As something of a consolation prize they were given a partly built Hols Der Teufel primary glider by the Southern Cross Club who had received it from the now defunct Sydney University Gliding Club. Timber, glue and unbleached cotton fabric were purchased and some set to work on the wings in Frank Geach's garage while others sawed and hammered on the fuselage in Jim Rawling's lounge room. His wife could not see the importance of this work!

But that was the way it was. Unless you were very flush with funds, if you wanted to fly you built it. And that could mean building things in some more unusual places. The author remembers visiting an enthusiast's house to learn some skills in finishing off our recent Hols der Teufel machine. The wings of his Grunau glider were supported down the hallway by pieces of wood nailed at right angles to the timber of the doorways. His two children had become quite adept at getting through the wing to go to their bedroom and the bathroom, and it seemed a most satisfactory way of providing a well-lit work space. His wife was not there at the time, having left some months previously for some unknown reason.

The Hols der Teufel project seemed to take an eternity to build, so before the machine was completed, the group decided to merge with the Southern Cross Gliding Club. Later the Hols was given to a group in the Hunter district who put the finishing touches to it then immediately wrote it off on the test flight with an inexperienced would-be pilot. The merger with the group and Southern Cross took place on 1st March 1954. On the 7th March the author had his first taste of training in a solo primary glider.

Early training was done with a short cable about 80ft (25m) long and the Primary was auto towed by an old Bedford truck, which meant you could never get much above 50ft high. Instrumentation in the Primary was sparse and consisted of an altimeter from the war disposal shop hung on a piece of wire inside the nacelle. If while on circuits the pilot wanted to know how high he was, he pulled out the altimeter, read it, then hooked it back on its wire again.

The flying instructor was a French-Greek from Egypt complete with the regulation battered briefcase full of drawings which he later unloaded on the Australian Air League. (A machine was built from the plans and it flew briefly at Schofields Airfield). Anyway our instructor explained in broken English how to climb into the machine and how he would follow the glider down the runway in his car so that he could tell you later what went wrong!

The first few tows were made at low speed so that the machine could not take off. However coarse movements of the controls could be used to keep the machine straight. After this the glider was lifted off the ground about 5 feet and held there. If the aspiring pilot got a bit too high or out of position, then the tow truck just slowed down and the Primary mushed back onto the ground.

After this the pilot progressed to higher and higher tows with straight ahead landings, until they put on the big cable and he had enough height to do a circuit. When he did a flight of over 30 seconds, he was awarded the "A" Certificate. All flights were timed with a stop-watch from cable release to landing. Later while on circuits, a flight by the author under a raging thunderstorm produced the absolutely amazing time of 3 minutes and 5 seconds, a club record.

The first Kookaburra was flown by Schneiders on 20th June 1954. This was a much higher performance machine, far surpassing the Kangaroo, and featured a 1 in 20 glide angle. At our Annual General Meeting it was shown that the club was on an upward trend with membership up from 11 to 22. We also had earned 3 "A" and 3 "B" Certificates over the year. Seeing it required no money, on the 17th September 1954 the club decided to place an tentative order for a Kookaburra. Meanwhile we would carry on with the Primary.

Kookaburra 2 Seater circa 1957

On the 21st November 1954 one of our members decided to do a hanger flight along the old cross strip (which is now the taxiway) at Camden. It was bad luck that the Sydney Soaring Club had parked their Tiger Moth tow plane right in the way, but our boy was able to continue on after crunching through the top wing of this obstacle. He then skidded around the corner to stop in a heap in front of the hanger and stepped out unhurt! Jimmy might at least have had the decency to break a leg! The primary was a complete write off.

At the end of 1954 the Dubbo Club held a gliding camp where instruction was available on the Club's recently built Venture side-by-side two-seater. Some Southern Cross members went along to find out about this soaring business. They included Charlie Treffner, Frank Hudson, Peter Cox and John Postlethwaite. The last three won their "C" Certificates at the camp.

On return to Sydney the three new "C" pilots purchased a Seabird sailplane from Queensland. It was the first private owner group to operate within Southern Cross. The machine was home-built and mostly home-designed, though the wing resembled the Grunau Baby in shape. It did some soaring but enthusiasm waned when an inspection inside the tail revealed some of the plywood used in the construction had "Norco Butter" printed on it. After all, in those days the lowest possible grade plywood was used to make butter boxes !

As the Seabird pilots were inflicting tales of soaring about in huge thermals on the other members, the Club decided to try and find a way to turn the tentative order for a Kookaburra into a firm one. The Primary was not repairable so if the club was ever to fly again, it was going to be by Kookaburra.

This was probably the most important point in the Club's history as we had to try and buy an aircraft for which we did not have the money. So what's new you might say? Well we also had no assets. And no bank manager in those days would think of lending a penny for a madcap scheme like buying an aircraft. (My how times have changed). Much of the club's success at this point was due to the then President Frank Geach. He organised money raising schemes, house parties and raffles. He reintroduced the "Members Loan" idea. Dr George Heydon, the Club's first President, came to our aid with a gift of 600 pounds, equal to almost a year's salary for a tradesman and a significant part of the purchase price. We were on our way!

While the club waited impatiently for the Kookaburra to arrive, two club members, Reg Todhunter and Stephen Martin (who also had a battered briefcase) opened Glidair Sailplanes at Bankstown on 16th May 1955. It was the first firm in Sydney solely for building and repairing gliders. They built a number of machines over the years including the club's first Grunau and a motorless Gyrocopter.

Finally the Kookaburra was ready for delivery. But the club had no trailer on which to transport it from Adelaide. The Sydney Soaring Club offered their Tiger Moth for aerotowing the Kookaburra to Sydney which was rather decent of them after the crunched wing episode. The towing was done by Ken Rogers. Bob Krick did the first half of the trip in the Kooka and Ron Sharp did the second half. Ron was later to be become well known as the designer and builder of the Sydney Opera House Organ. The aerotow combination finally arrived in Sydney in November 1955 after the longest aerotow in Australian history.

Bob Krick checked out CFI Harry Ryan and new member Werner Geisler on the Kooka and our club was ready to start instructing. The Kookaburra was named "Heydon" in honour of Dr Heydon for his donation towards its purchase. For many years the Kooka had this name in white on both sides of the fuselage.

Now people came from everywhere to join so the club decided to limit membership to 40. This was the first time the club had more applications than it could handle. At the suggestion of member Merv Waghorn, an Instructors Panel was formed. We were launching the Kookaburra by winch and new skills were to be learnt. Many migrants joined the club and these skilled people brought a new insight to the club. Until a couple of years ago, the whole source of gliding information came from England. In a major shift in club thinking, we suddenly found that we could benefit from a wide range of ideas from everywhere. Many brought years of experience and told tales of clubs trying to fly gliders in WW2 in Germany. Fred Heumann described how his club was pressed into service in the closing stages of the war. His club had a winch and a Grunau Baby sailplane. By taking off the windscreen, bolting a machine gun in its place, the machine was winch launched to about 800ft where it could spray troops on the other side of the river before a hasty circuit to land and prepare for another effort. Gliders had been used to carry troops, but this surely was the first time a sailplane had been used for this!

The first Southern Cross winch circa 1957

In February 1956 our first woman member Irene Postlethwaite, joined the club. She won the club's first female "C" Certificate 12 months later. In May 1956 the club took delivery of its first solo sailplane, a Grunau Baby from Glidair Sailplanes. The next addition was the ES57 Kingfisher from Schneiders in September 1957. The club was now going ahead in leaps and bounds and more members were admitted. Roger Woods joined us in 1957 to start a long involvement with gliding.

At Christmas 1957 the club held its first camp away from Sydney for the purpose of getting some Certificates. It was held at Narromine and all three machines were taken along. Our cross-country experience was zero but after doing things the wrong way a few times we soon learnt better. There were many theories that were put to the test during this camp, such as the one espoused by one hopeful member. It went like this. If you had a positive enough attitude when you got to the top of your 1200 ft winch launch, you wouldn't wait to gain height in lift, but should set off on course straight away and you would find lift simply because of the greater distance you travelled from the aerodrome. He tried it, went half a mile and landed in a well used cattle yard, and was finally retrieved 4 hours later after a drenching thunder storm. That theory was abandoned.

By 1958 people were starting to look at the safety record of the club. We had expanded very quickly but still had the old slap-happy approach to flying. We had 3 major crashes with the Grunau and one with the Kookaburra all in 10 months! Still they said these things just happen and the free and easy ways continued. It was not unusual to brush the tops of the trees on approach to land and so long as the machine finished up in one piece nobody minded.

In 1958 the club had 72 members, made 1426 winch launches for a total of 238 hours. It had 3 machines, 2 winches and 2 trailers. But in 1959 the tragedies started to catch up with us. In January Secretary Mike Taylor was killed. In February exCFI Harry Ryan. Then in April Hinkler Club member Fred Hoinville. In November the Grunau was written off when it collided with a parked car on the aerodrome. Some rules were made but the standard of flying did not improve much.

A new Grunau was purchased to replace the earlier one and in March 1960 the ES52B Longwing Kookaburra was bought. The first issue of the Club Journal appeared in March 1960 edited by new Committee Member Roger Woods.

In 1961 the GFA took over the now defunct "Australian Gliding" magazine which ex-club member Allan Ash had started in 1951 and struggled with for so long. In January 1961 Jean Dines became our first woman club member to gain a Silver C.

Then Ron Adair arrived in Sydney. As an experienced CFI from Adelaide, he was shocked by the crashery rate and the flying discipline. On 14th April 1961 he became CFI and started a safety campaign. The club started to use the take-off drill "CHAOTIC". Ron became the most unpopular man in the club when he grounded people for knocking leaves off trees with gliders. He was even more unpopular when he put people back on dual because they were unsafe. But the crashing of machines stopped.

A move was started on 29th March 1961 to make out a new Club Constitution which would clearly define the club's and members' rights and obligations. We tried to make it cover every possible situation which could arise. After innumerable rewrites it was finally adopted eight years later in June 1969.

By the end of 1962 our membership was limited to 100 flying members. Aerotow was being seriously considered as an alternative to winch. However the massive cost of a tow plane was beyond our reach. To help the club, one of our members and a great benefactor of the club, Trevor Kyle, offered in June 1963 to purchase an Auster himself and hire it to the Club at nominal rates. This wonderful offer put us into the "Aerotow Age". The same year we purchased an ESKA6 - a Schneider-built copy of the German KA6. And Mal Williams and Ron Adair were made Honorary Members.

In June 1964, Trevor Kyle offered the Club the Auster on no deposit, no interest and 10 years to pay. Naturally we jumped at it. We were now using both winch and aerotow launching methods. About 90% of all launches were still by winch along side the main runway, which was cheap and efficient, and the few members who could afford aerotows were mainly solo pilots. But as take-offs and landing are what it's all about, winching had a lot to offer. We had two winches, each single drum trailer types, although we had tried multiple drum and self-laying winches over the years. Winching was very labour intensive and effective, providing the cable didn't break and disgorge coils of wire all over the runway effectively blocking it until the cable could be carefully straightened up, joined and wound back up, often an hour later. Understandably the few power planes who were now in evidence at Camden began to object to our winching operations.

In September 1964 we purchased the Polish manufactured Mucha. And as Glidair Sailplanes had gone out of business years ago, George Detto started a glider repair business at Camden in November 1964. At Christmas, Club members had a taste of National Competition flying. John Blackwell came second and won a place in the Australian team at the World Competitions in England. Another first for the Club.

The Club now concentrated on modernising its aircraft. The Grunau was given to the Forbes Club, though even this proved to be a costly exercise. It was decided that if we were to give a machine away to a club, such as one which had been very hospitable to us at our camps for many years, then it should be fully overhauled. So it was renovated completely and given a nice coat of paint. Everything had been arranged so that the hand-over would be done at our Christmas Forbes Camp. The local press were to attend and there would be much hand shaking. The day before the hand-over, one of our pilots argued with a fence while landing the machine and it had to be taken to Sydney, extensively repaired and trailered all the way back to Forbes for presentation half a year later.

Then we moved into the era of rugged higher performance training machines. The first K7 was purchased on the 21st March 1965. A year later in April 1966, the second K7 arrived, and the ES52 Kookaburra was sold to the Khancoban Club. It was sad to see the old "Heydon" leave the Club after 11 years, particularly as it represented the starting point of Club soaring, and the incredible efforts of so many people to buy it in the first place.

The small light Kingfisher was sold in November 1966. It was bought by an enthusiastic fellow who believed in being totally self-sufficient in life. He arranged to give himself winch launches from a convenient hillside in the Snowy Mountains, so that he could hill-soar initially, before progressing to better lift. He launched by fitting a quick release onto the tail of the Kingfisher and mounting a matching ring on a post in the ground. He attached a another ring and a series of car inner tubes to the belly hook at the front, and then a length of rope on to his Land Rover. He would start the Land Rover in low gear low ratio and go back and strap into the Kingfisher while the inner tubes slowly stretched out. The Land Rover stopped down the incline when the predetermined amount of petrol ran out, and then it was simply a matter of operating the tail release with a piece of string and it was up-and-away. If the lift was good, he could land back at the top and all was well. If he landed at the bottom of his hill, this rugged fellow would walk up the top, hitch his special one-man trailer to the Land Rover and go down to load the aircraft on to it. He wrote up a description of this in Australian Gliding and was surprised at the reaction he received.

ES-KA6 in 1964

At the same time the first Super Cub tow plane arrived and the Club went almost fully aerotow. Although the asthmatic Auster had done its best, the Super Cub offered a more powerful engine with a metal propeller, and above all reliability. There was a tremendous effort put into utilising the tug every daylight minute so that a bare minimum launch cost could be offered. Ingenious schemes were worked out to ensure that machines were ready to launch and the tug was never left standing with its propeller turning. The record number of launches for a day with just one Super Cub was 104 at the end of 1966. It was not long before we had two Super Cubs, and the winch was put in the back corner of the hanger. But despite an extra tug, operations became more relaxed and the launch record has never been broken since, even when we had four tugs on the field!

The club looked at improving the use of our assets by encouraging flying during the week. John Postlethwaite and David Head organised, advertised and ran the first Monday-to-Friday instruction course in November 1972. After proving there was a demand, the idea caught on and the club employed our first full time instructor, John Blackwell. This led to mid-week flying groups starting and a seven-days-a-week operation. It became clear that we could not afford our aircraft to be out of action at weekends and that ongoing maintenance would have to be co-ordinated with the weekday flying activities. Dennis Mathews and John Postlethwaite advertised widely in Australia and overseas for our own Maintenance Engineer. Tom Gilbert came up tops and came to work for us in 1973 and later started his own business at Camden.

Motorgliders were beginning to be seen as a quick and easy way to train people to solo and in February 1973 we purchased an Fornier RF5B motorglider. This would no doubt be an excellent private owner machine in cooler Europe, but with overheating difficulties and no apparent shortening of the training time for students, we sold it in February 1976.

Next came the Pawnee tow planes with 230HP engines, each of which were undoubtedly able to do the work of two Super Cubs. The launch time dropped dramatically, particularly on those days of widespread sink. But the number of launches has never approached our record. But we fly on…

The Old Bedford Truck used for auto launches circa 1956

Ah…. So that's how it all happened. Ah… How things have changed.

When we look at our fine fleet of sailplanes and tugs, some of them world class machines, it seems ages ago that the pride and joy of the Club was a Primary glider being dragged along a paddock by an old Bedford truck.

Yet our Club has come a long way since January 1948 (or July 1944 if you go back to the "real" start). And its assets are not just the hardware side of things. It's the know-how and experience, the extremely high safety standards, the teamwork and sheer effort of the past, that make the Southern Cross Gliding Club what it is today.

Southern Cross RF5B Motorglider in 1973

I always hope our new people joining will spare a thought for the history makers that pointed us along the right path, because our new members now will in turn become the history makers for tomorrow.

An extract from Miro Vitek's biography 'Alive in Australia'

In the strange workings of the Public Service Board, I was appointed as permanent Class 2 in Brisbane, since there was a slot for that position there. Eventually extra Class 2 positions were created for New South Wales, and only then I became permanent at Bankstown. But my seniority as Class, 2 started from the time of the Queensland appointment, although I was never asked to take it up.By this time I was sufficiently versed in the workings of the Public Service, the Gazette, the protective appeals that had to be attended to every time there were promotions or transfers going round. There were some stories of how the Department could transfer an officer against his will, but they turned out to be just stories. Somebody was always ready to change places or pursue a promotion to fill an advertised vacancy. Some stations had bad reputations, such as Tamworth or Canberra. Some were considered plum positions, such as anything in Tasmania or Queensland or South Australia. In many cases it was a case of the grass being greener on the other side of the fence. The problem with these outstations was the slowness of promotions. People there tended to be forgotten. Usually the highest grade was Class 3, and that would be a supervisory position. One tended to lose the feel of the pulse of the mainstream in the Department.After Schofields I yearned to have my own show again, so when rumours started to spread that Camden and Tamworth positions were to become vacant, I let it be known that I would be willing to take over Camden Airport. The rumours were confirmed officially and my application went in. There were only two other applicants and neither of them was from the New South Wales Region.

In due course I received a letter from the Regional Office stating that I had been transferred from Bankstown to Camden Airport with effect from 18 July 1969. After the official handover-takeover, I was to assume the duties of ATC/OIC (Air Traffic Controller and Officer in Charge) of that Airport.

Air Traffic Controller is a licensed position. I had that with airport controller ratings for Bankstown, Schofields and Camden. Officer in Charge was an administrative position, a step below Airport Director (the OIC position is now abolished). The combination of these titles resulted in an effective and powerful position. In many ways the OIC had more power and say in the administration of an airport than the Airport Director. I had to become a Collector of Public Moneys (a Treasury appointment), a Keeper and Receiver of Stores, Ordering Officer, Administrator of Commonwealth Property, Clerk, Postboy, all for the princely allowance on top of my regular salary of $185 per annum. This was not much, but it opened many a door, the existence of which I was not even aware.

Camden Airport was originally a private airfield owned by Mr Edward Macarthur-Onslow and established by him and his brothers in about 1934. It became a fully established airfield with hangars and a Flying School (Macquarie Grove) in 1938. In 1939 the airfield was offered by Mr Edward Macarthur-Onslow to the Commonwealth Government and has remained in its possession every since.

During the war more hangars were built, as well as the long bitumen runway. When the war ended the airfield became redundant to the Air Force and reverted to civilian use.

After World War II, life in Australia returned to the pre-war style. Changes came slowly. During the 1950s and 1960s, life was regulated by the weekend. Sports were played on Saturday, with churchgoing, and gentler sports on Sunday. Commitment to sports such as gliding required at least one whole day, if not the whole weekend. Gradually the gliding fraternity moved in to Camden, flying from the verges of the runway mainly at weekends. Powered aircraft traffic, which never abandoned Camden, started to use it more and more, as Bankstown Airport was becoming saturated at weekends.

Operations at Camden became sufficiently complex to warrant re-establishment of civilian airport control. This the Department did in 1962. Mr R Imber was the ATC/OIC until he handed the station to me.

Camden thus became the only airport in Australia where gliding and general aviation activities were conducted from the same field. Since each activity had conflicting problems, the need for re-establishment of control became obvious. Unfortunately, there were no rules in our manuals on how to eliminate these fractions and problems. The Department was extremely conservative, and its unwritten opinion was that gliding and power flying were not compatible. This was exacerbated by the Departmental system that allowed gliding activities to be self-governing under their own nationwide organisation, the GAF (Gliding Federation of Australia), which acted on behalf of autonomous State gliding associations. The jealousy among the clubs, combined with the loyalty of members to their clubs, made it nearly impossible to control combined operations.

The Department hoped that gliding was only a fad that would eventually disappear if only the control could be made more unpleasant, hastening the end by attrition. This could not be declared publicly, as some politically powerful people were involved in the sport. By not making it easier for them, it was hoped that they would tire of the pressure. In this spirit control was imposed in 1962 at Camden, control that definitely did not favour gliding in any way, control that was inclined to show it as a nuisance, a source of complaints, and it was imposed rigidly.

The distrust between the gliding people and the Department was palpable. Those of us who came from Bankstown once in six weeks to do the afternoon shifts at Camden were not aware of this, as no glider pilots came to talk to us. We were all branded with the same iron. Small suggestions of improvement were met with the same reply that there was a system of operations that had stood the test of time, and that was it. This ultraconservatism can be seen in one of the letters by that favourite of mine among supervisors, Ray Harris, in which he stated that the controller should ensure that only three gliders were airborne at any one time. I did not realise how full that can of worms was when I so cheerfully became the OIC of Camden.

First let me briefly describe the administrative side and then the operational side of the workings of Camden Airport.

My working week consisted of five days: Saturday and Sunday, the morning shift at Camden; Monday, a morning shift in Bankstown Tower; Tuesday and Wednesday, rostered days off; Thursday, administrative day at Camden; Friday, afternoon shift in Bankstown Briefing. If there was a public holiday, I did a day shift at Camden. Each shift was eight hours, nonstop, except on public holidays when it was nine hours, extended usually by the demands of traffic to ten hours. This lasted for six years, after which I got my own Air Traffic Control staff, thus ending the dependence on Bankstown staff to fill the afternoon shifts at weekends. Then we were all able to have one weekend off each month.

We had a well-equipped fire engine on the station manned by firemen from Bankstown. They operated only during the busiest part of the day. My responsibility to them was only in ordering the materials to keep the fire tender operational, such as petrol, foam-making material, etc. The fire service was eventually withdrawn from Camden for reasons of economy.

For general maintenance I had three groundsmen with one truck, one utility, one tractor, one grader, a grass-slasher and all the bits and pieces needed to maintain an airport. I was fortunate to have as Senior Groundsman Mr Jack Devitt, an able and honest man.

Then there was the store where we kept the required number of hand tools, nuts, bolts, fencing wire, lanterns, markers, soaps, toilet paper (for public toilets), paints (airport markings consume large volumes of paint), etc. Last we had a fuel store for the petrol, dieseline and oils to run our vehicles, and kerosene for runway flares.

All. this needed mountains of paperwork, as most items were on my charge, entered in a proper accounting book where it could be checked twice a year by auditors. I even had to inspect the men's overalls and boots to see whether they were sufficiently worn out to warrant an order for new ones. Most of this paperwork could not be postponed as it consisted mainly of the weekly, fortnightly and monthly returns. At a large station one would have a clerk to do it. No such luxury for me. Towards the end of my tenure, as the old system was being dismantled and the demand for statistics etc. from Canberra rose, I was allowed to hire part-time office help.

The Department of Civil Aviation was large. It owned the airways and it owned the airports. It had its own engineering staff, flying staff, planning staff, construction staff, maintenance staff, operation staff, mechanics, electricians, stores on all levels starting from Central Office through Regional Offices down to the local level.

I soon learned how to navigate this maze and who were the right people to approach. I also learned how to work one section against another to achieve the results I wanted. This took time, and there were many failures and mistakes. However, in spite of all this bureaucratic weaving and shadow-boxing, it was a lot of fun.

If there had been no gliding, Camden would have been just another one-runway, uncontrolled country aerodrome. The gliding clubs moved there because it was under-used, hangarage was available, it was maintained to a high standard and it was free. Not even a peppercorn rental was required. It was obvious that if the Department could get rid of gliding, it would save all that trouble and expense. To that end the Department even tried to help with the purchase of another gliding site, but to no avail. I started to wonder how permanent my sojourn at Camden would be.

The problem with gliding operations was the method of launching. Most of the launching from the beginning was by winch. This required the longest possible run, which meant that gliding had to take place from alongside the runway. The main disadvantage of winching is that it is not compatible with other flying from that runway. The wire is invisible, and any collision with it means instant death to the colliding aircraft. The other disadvantage is that the wire has to be retrieved by a motor vehicle, which constitutes a hazardous obstruction to aircraft landing on or departing from that runway. If the launching wire landed on the runway, usually in large coils, the runway would be unusable until it was removed. The retrieving vehicle dragging back the wire tended to make rough tracks in the grass verges bordering the bitumen runway. Originally two winches operated, one at each end of the runway. It was difficult to feed a powered aircraft into this wire trap. By the rules of air navigation, a landing aircraft has priority over departing aircraft; thus if there were three or four determined people in power aircraft doing circuit training, they could effectively stop any launching of gliders. At times this was the norm, and one could imagine the frustration of the glider pilot sitting in a hot cockpit for anything up to twenty minutes waiting for a gap in the traffic.

There were some attempts to launch an aerotow, but it was expensive and the aircraft used (Tiger Moths or Austers) were not suitable for the purpose. The Southern Cross Gliding Club eventually took the plunge and purchased two modern aircraft with acceptable performance (Piper Super Cubs) and became purely an air launching club. The other club, Concordia, retained its winch although its members soon lost their reluctance to purchase an aerotow launch. Although this increased the rate of glider launching and reduced the danger of wire-strike, it created another frustrating situation.

There is another long-standing regulation, world-wide, that power gives way to glider (sail has priority over steam). As soon as the glider was on base, a power aircraft on final had to go round or orbit to give way, which was frustrating in training and expensive for the power pilot. This was why the two sides of aviation could not see eye to eye. As a matter of fact, they hardly spoke to each other.

Four parachuting schools or clubs operated from Camden, but apart from complaints of delays in their departures they created no problem as their drop zones were some distance from the control zone of Camden.

It required an iron will to regulate this dangerous circus of weekend traffic at Camden. In 1962 the Department issued a directive that there must be no gliding at Camden without a controller. I decided to do the best the situation offered and carry on.

I doubly strengthened my resolve not to accept any freebies. There were three flying schools at Camden, two gliding clubs and four parachuting schools, also some traffic generated by occasional flights from Bankstown. As it happened, my resolve was easy to keep. There were no offers of anything free for the time being.

The Chief Flying Instructor of the Camden Aero Club (which also operated mainly a weekends) was Bob Curtis, an acquaintance from my time with the Royal Aero Club of NSW. He was the first person from the flying side at Camden to welcome me with warmth. We became good friends. During the week he was a high-school teacher, later an assistant principal, and indulged his love of flying through instructing at weekends. The other flying schools were just politely friendly. Another man whom I came to know well was a German immigrant by the name of George Detto, who had a glider repair business in one of the hangars. I knew only one other man who was also connected with gliding, Maurie Bradney, an instructor and charter pilot with Rex Aviation at Bankstown.

The Senior Groundsman, Jack Devitt, became the most helpful and cooperative workmate that I could desire. I do not know how I would have managed in the first six months without him. Jack was about five years older than me, a man of tremendous capability, good knowledge of machinery, even temper and absolute honesty. In stature he reminded me of the 'Man from Snowy River', except that he rode no horse.

So it was that with the tentative threads of these casual acquaintances I started my moves to reshape Camden. First I decided to be friendly with the gliding people, as the only contact I had with them was when they sent a junior member to pick up the small radio and the weather forecast in the morning and to return the radio in the evening. To that end, when I finished the morning shift, I made a point of going onto the field in the official utility to visit their operation. There was nothing but icy silence. No one came to introduce himself or say hello. This went on for several weeks until I decided it was a waste of time. I must be as strict as my predecessor and let them make the first move. I could see no solution to the flying situation, nor could they.

Their move came soon. One Saturday morning a man arrived at the tower, introduced himself as Ian Turk, President of the Southern Cross Gliding Club, and welcomed me to Camden. He told me he hoped we would have a fruitful association and that the Committee had decided to offer me free flying in their gliders until I reached solo standard. I was taken by surprise by such sudden forwardness from a gliding member. I thanked him for the offer and explained that I did not accept free flying, but if I eventually decided to do any flying, could I pay for it at the same rate as any club member. (I had heard that joy flights in a glider were hard to get and were at a much higher rate.) He said he would pass that message on to the Committee at the next meeting, but meanwhile he gave me his telephone number in case I needed his assistance in relation to his club. The old saying, 'Beware of Greeks bearing gifts' passed through my mind as we parted.

How I misread that man! As I came to know him better, there emerged a person who was a wheeler-dealer, but of such warmth and sincerity that I felt guilty for doubting him. We became good friends, and I believe he was one of the best presidents of that club, if not the best.

Ian was of Czech origin; his family managed to get to England before the onset of World War II. He saw service in the RAF during the war as a Lancaster bomber pilot. Presently he was an engineer with Comeng at Clyde (rail locomotives). I also found out that the Committee had not decided to make that offer but later went along after Ian told them he had made it to me knowing they would approve of it.

I related this conversation to Maurie Bradney when I saw him next at Bankstown. He approved of my refusal of free flying but advised me to try and solo a glider, as it would break the ice and 'You never know, you may perhaps help us.' I said I would think about it.

For the time being, even if I had some constructive idea of how to solve the problem of the power aircraft and glider operations, it would have been useless. My supervisor, to whom I was directly responsible at the Regional Office, was still Ray Harris, who had his own ideas (get rid of the gliders) and who demanded blind obedience. I had to give a dressing down to a controller from Bankstown because he accommodated gliders on one windy day in other than the prescribed direction. I felt as if my brain was shrinking. So I decided to coast a little.

I felt I should concentrate my attention on some urgent problems at the airport. I made a list of them. At the top of the list was the state of the women's public toilets. My wife, on a visit to my domain, drew my attention to their inadequacy and shabbiness.

The public toilets were relics from the war days. While the men's toilets were adequate, the women's were not, consisting of a corrugated-iron enclosure with no roof and only two cubicles. There were no handbasins, no mirrors. light at night was supplied by a street light on a nearby power pole. The airport had its own sewer system with a pumping station to pump the effluent across the river to the municipal sewage treatment works.

I wrote to the Regional Office ('attention Building Section') and in due time somebody arrived to inspect the 'building'. Some weeks later a letter arrived allowing a sum of $600 towards the maintenance of the building. That would have hardly paid for the painting and replacement of a few rusting corrugated-iron sheets. I wrote a stronger letter stating that I had in mind rebuilding and not repair, and that the minimum requirements were a new building with at least five cubicles, two handbasins and two mirrors, with internal lights operated by a light-activated switch. Back came the reply that no money was allocated for new building at Camden Airport. It was $600 or nothing. However, my request would be submitted for possible allocation next year. I replied that the need was now and threatened to take pictures of women standing in a queue to use the facility. All this was to no avail. No money was allocated to new building that year. In later years I came to realise how hard it is to obtain an allocation not requested a year before. This was the cause of much frustration. However, I do not take a knock-back readily.

When I finished the office work on Thursday, Jack and I would go to the local pub. Sometimes the other groundsmen joined us. Jack introduced me to a man who used to sink a few in the same pub; he happened to be the local Water Board Health Inspector. After a few beers I asked him to come and inspect the toilets and perhaps write me a letter of condemnation. This he did and I forwarded it with another request to the Regional Office. Within a fortnight plumbers and carpenters arrived, built a temporary toilet for the women and demolished the old one. A new concrete base was poured and a new building with five cubicles, basins, mirrors and lights was erected. My happiness and that of all the women was complete.

I asked the project supervisor where the money had come from. Building maintenance, he said, because they covered the original concrete base with a new base, claiming the old one was cracked, hence in need of repair. There seemed to be always money for maintenance, this time to the tune of $7000. Eventually the men's toilets were rebuilt on the basis of the need to replace the old concrete urinals with new, up-to-date stainless steel, again with maintenance money.

At the end of March 1970 the Air Safety Investigators organised a glider flying experience week with the Southern Cross Gliding Club, the cost to be borne by the Department. One day one of the investigators could not attend, so I was invited to fill his place. According to my log book, on 23 March 1970 I had five instructional flights in a glider with Roger Woods, a senior instructor with the club. This was the beginning of my long association with Roger and gliding. We came to understand each other well and cooperated towards my eventual solution to the problem of operations at Camden.

After this I continued to fly a glider about twice a month, after the morning shift, with other instructors, and on 12 June 1970 was checked out and sent solo by Maurie Bradney. By this time the gliding fraternity were nicer to me and the original frigidity was a thing of the past.

It was customary for the pilot on his first solo in a glider to shout the drinks at the end of the day. I paid for well over fifty schooners of beer that evening in Donnelly's pub at Narellan.

The other club, Concordia, also offered me flying in their aircraft under the same conditions. I gratefully accepted. Later, when I became more involved in gliding and flew gliders from both clubs, I paid one membership fee but gave half to one club and the other half to the other. I did not get hooked on gliding until I started to soar. It is a very exciting but also a very selfish sport.

Contrary to my hopes, my glider flying did not shed any light on the solution to the operations at Camden. However, it did highlight the need for something to be done, and done very soon. I could see the reason why the glider pilots and the power pilots did not like each other. It was because they were forced to use that narrow strip of ground where they were in each other's way, tripping over each other, causing delays and at times endangering each other. As the hangaring of aircraft belonging to non-profit clubs was free, the gliders had to share a hangar with the aircraft belonging to Camden Aero Club. There were arguments at the end of each day's flying. Not that there was any shortage of hangar space at Camden. It was the way it was distributed. It was obvious that this problem would have to be tackled at the same time as the flying problem. A glider is an object of grace when flying but an awkward, inert piece of machinery when it lands. It has to be manhandled out of the way of other aircraft.

It had become obvious, even to the most enthusiastic, that after about 9 a.m. the winch was useless. Consequently both gliding clubs were aerolaunching. In order to understand the whole operation, I also obtained a rating to aero-launch the gliders.

I tried to pick the brains of other flying people, both at Camden and at the Regional Office, for a solution, but to no avail. One man from the flying section at the Regional Office suggested that the flying be regulated so as to ensure a whole hour of uninterrupted flying for power aircraft, followed by an uninterrupted hour's flying by gliders, repeated in that order during the whole day. This went down like a lead balloon. Even if I had discovered an answer, I doubt that I would have been able to push it through the entrenched stubbornness of my regional supervisor, Ray Harris. Consequently I decided, for the time being, to follow my rule of doing the best one can in the circumstances, be always alert for any changes, and the solution would present itself in a flash, even if that flash took some time.

First a solution to the hangar accommodation presented itself. As OIC I had a wide field of influence here. There were no formal leases to the hangars, some being allocated just by letter from the Regional Office. One hangar had an Aircraft Museum in one half; the other half was leased to the Nepean Flying School. The museum was run and owned by Mr Harold Thomas, his wife and son. The Thomases were a charming couple; their museum was well run and all the exhibits were excellently presented. Harold had been an aircraft engineer in World War II and, as far he was concerned, no decent pilots had been trained or good aircraft built since that war. He was also a bowerbird. His collection became bigger and bigger, necessitating expansion. He applied for and received permission from the Property Section at the Regional Office to expand some of his exhibits in the adjacent hangar used by the gliding clubs and by the Camden Aero Pub. Who was going to squeeze whom out? When the complaints became virtually unbearable, a directive came from the Region that another hangar was to be repossessed as the-company leasing it had defaulted in their rent and had gone bankrupt, and I was to break the padlocks, change them and take possession of the building. This was well within the powers of the OIC. Upon gaining entry into this hangar, I found it filthy, full of old crates, papers and junk, among which were two partially cannibalised fuselages of Sycamore helicopters (ex-Navy surplus) of no commercial value, and a set of rotor blades out of hours. I offered them to Harold for the Museum in exchange for cleaning the hangar. He accepted. Later he acquired another similar type of craft that had been vandalised at Bankstown, complete with a hoist, and from these pieces he has in his Museum a complete Sycamore with all details.

I had now a spare hangar into which I told the gliding clubs to move, with the understanding that some rent had to be paid. As it turned out, it was only a peppercorn rent. The gliding clubs thought all their birthdays had come at once. From now on they could fight for the space only among themselves. Later another company that did aerial surveys went bankrupt, which gave me another hangar into which I was able to accommodate the Camden Aero club, the Home Builders' Aircraft Association and later the National Parks and Wildlife Service. After this effort, the gliding clubs and Camden Aero Club looked upon me as a miracle maker. Later Marshall Airways removed two of its disassembled DC-2s from another hangar into which I persuaded the gliding clubs to move for their own benefit Thus the problem of aircraft accommodation was solved temporarily to everybody's satisfaction.

In 1970 there were unexpected changes in the Air Traffic Supervisory Personnel at the Regional Office. The three top positions were filled by promotion of men from Sydney Airport with whom I was well acquainted, some of whom were to become friends. These were Bob Lambert of Flying Operations, Max Press, Regional Supervisor of ATC and John Renshaw, Regional Supervisor of Standardisation and licensing. They played an important role to the end of my days in the Department. I was on first-name terms with all of them. Ray Harris accepted a promotion to the South Australian Region and, while I got on well with him, his ultraconservative views were a potential brake to my plans for Camden, which had started to germinate in my mind.

I came to realise that no solution to my problems would be forthcoming from the Regional Office hierarchy. There was nothing in the 'books' covering combined gliding and power operations at government airports. The only effort towards a solution so far was the application of attrition. Make it harder for them and they will move away. Early in 1970 the gliding clubs were given three months' notice to vacate Camden. This was later rescinded on the understanding that if a decision was made for them to leave Camden they would have to vacate within one month.

Yet the solution was there for all to see: get away from all that milling around the one runway; make two aerodromes from the existing one. Why abandon one perfectly good half of the aerodrome to three-foot grass and red-bellied black snakes and hares when it could be used for gliding activities? Separate the two warring factions on the ground and in the air by having one operate to the north and the other to the south, always turning in the opposite direction to each other. Two airports in one.

I submitted my first tentative proposal for a partial solution to Ray Harris as early as the middle of October 1969 in response to his request to me for the temporary removal of gliders to allow the grass around the main runway to regenerate, as through constant use that area had become bare and eroded. I was still bound by the rule that everything must move in one direction; thus I proposed a circuit within a circuit. It was a crude proposal and mercifully was allowed to die on Harris's desk without a reply. The only record of that feeble effort is in my Camden file and I cannot help blushing whenever I read it. But at least I made a start.

About this time Ray Harris left the NSW Region. He was replaced by Max Press, a completely different personality. He was very approachable; one could call him unflappable and even-tempered. He never put you down; an excellent handler of subordinates.

I felt I had reached a dead end. My first effort was only something to be ashamed of and the more I tried the more I seemed to entangle myself in a web of possibilities.

Christmas of 1969 came and as usual the gliding club packed up and went to the summer gliding camp in Forbes, giving me a much-needed respite and a taste of how good it would be if the gliders were removed from that accursed runway. It was so pleasant. No snide remarks about delays from the power people. Bliss

During this time the BP England to Australia air race was held. The Department was in a dilemma because of this race. It was a light aircraft race open to entrants from all over the world. However, the Department did not recognise foreign instrument ratings for ordinary pilots unless they were the holders of an airline transport licence. Therefore, if anywhere over Australia-the race was interrupted by bad weather, it would guarantee a win by an Australian, as they would have been the only ones to fly legally. That would have amounted to playing the game with loaded dice.

The Department overcame this by reserving a block of airspace over the race route within which the pilots could fly in any way they wished. That would have been fine except for the very last stage of the race, which was to finish at Bankstown Airport. The solution: reserved IFR airspace from Adelaide to Griffith, Cowra and Camden, where the pilots would have to establish themselves visually and then proceed visually to Bankstown. If the weather was bad, they were all to land at Camden. Excellent! Unfortunately Camden had no radio navigational aid to which the pilots could tune. There was a spare NDB (non-directional beacon) in the store at Marrickville that could be erected temporarily at Camden. It was a rush job and I enjoyed the heated arguments between the Airways Engineering bosses as to the siting of the beacon. The installation requires some space as it consists of two tall radio masts and a big earth mat of copper wires. The navigational aids people chose a site right in the middle of the planned, future parallel runway. The airports people objected strongly. The argument was settled when the airports section had to admit that they had no money allocation for the extra runway and no chance of it ever being allocated. They were pacified by the assurance that the NDB was temporary and could be dismantled in a month or so if required.